Penal Times

The Meath Field Names Survey form specifically asked people to tick a box if they knew there was either a Mass Pass or a Mass Rock in the field.

In the findings about 20 Mass rocks are noted and over 200 fields are identified that had a Mass pass or path. In some cases the surveyor went to the trouble of drawing in the exact route of the Mass pass on the townland map they were working on. These paper maps will be archived with all the original survey sheets at the Local Studies department in Meath County Library. It can be seen that many fields with Mass Paths also have stone stiles.

There are about 13 references to Hedge Schools in the data collected through the project. Given that these Hedge Schools were so temporary in nature, it is truly amazing that so many details about them have been carried through in field lore until the present day, including the ‘Masters’ names in many cases and, in a some cases, even the fees paid by the students.

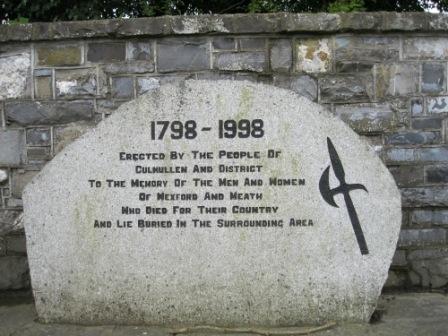

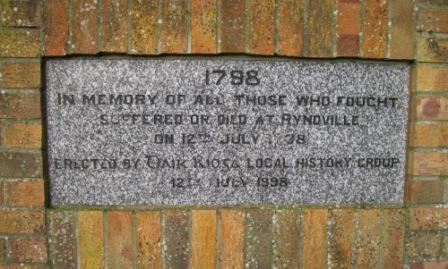

1798, Croppy Graves and Memorials

In 1798 many Wexford men died on expedition to Meath. Most of them were buried where they fell; some were only covered in shallow graves by local people. Many of the graves were marked with large stones, some of these memorials also took the form of crosses. In some cases more recent memorials have been erected on or close to Croppy graves. Often these memorials are located on the roadside adjacent to the fields where the Croppy graves are. Many of the newer memorials were erected in 1998 on the 200th Anniversary. The areas and townlands where 1798 activity and Croppy graves are referred to in the Meath Field Names Survey tie in well with the route of the Wexford Army as shown on a map in Eamon Doyle’s book, March into Meath: In the Footsteps of 1798.[1] The information regarding Ongenstown, Killallon, Moynalty and other areas west of Navan is not noted by Doyle in his publication.

Famine memories in Meath Fields

The Famine has firmly left an imprint on the landscape of Meath and on the people who inhabit it. There are almost 100 separate references to the Famine in fields surveyed through the Project. There are many mentions of Famine ridges, somethimes also known as lazy beds.

The impact of the Famine Relief work around the county is still very much in evidence. The work of road building, wall building, river straightening and even possibly the construction of a man made fox covert are all mentioned. It is poignant that several roads in the county that were built as famine relief work are still known as the ‘New Line’ today, over 150 years later.

The remains of famine villages are noted in several fields. In some cases the house outlines and other features are still clearly visible. It is amazing that they have lasted untouched for so long with all the modern farming practices. Sadly, there are also many mentions of burial places in Meath fields from famine times.

There are also a few references to the Workhouse at Dunshaughlin and the Alms House at Kildalkey both closely linked to the Great Famine in Meath.